D-Lib Magazine

January 1999

Volume 5 Number 1

ISSN 1082-9873

A Common Model to Support Interoperable Metadata

Progress report on reconciling metadata requirements from the Dublin Core and INDECS/DOI Communities

David Bearman

Archives & Museum Informatics

dbear@archimuse.comEric Miller

OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc.

emiller@oclc.orgGodfrey Rust

Data Definitions

godfreyrust@dds.netkonect.co.ukJennifer Trant

Art Museum Image Consortium

jtrant@amico.netStuart Weibel

OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc.

weibel@oclc.org

Abstract

The Dublin Core metadata community and the INDECS/DOI community of authors, rights holders, and publishers are seeking common ground in the expression of metadata for information resources. Recent meetings at the 6th Dublin Core Workshop in Washington DC sketched out common models for semantics (informed by the requirements articulated in the IFLA Functional Requirements for the Bibliographic Record) and conventions for knowledge representation (based on the Resource Description Framework under development by the W3C). Further development of detailed requirements is planned by both communities in the coming months with the aim of fully representing the metadata needs of each. An open "Schema Harmonization" working group has been established to identify a common framework to support interoperability among these communities. The present document represents a starting point identifying historical developments and common requirements of these perspectives on metadata and charts a path for harmonizing their respective conceptual models. It is hoped that collaboration over the coming year will result in agreed semantic and syntactic conventions that will support a high degree of interoperability among these communities, ideally expressed in a single data model and using common, standard tools.

Introduction

The Dublin Core Element Set (DC) was defined to support information discovery in the networked environment. The name "Core" indicates an assumption that DC will coexist with other metadata sets. Perhaps because of the focus on defining a simple semantic for the DC element set, it sometimes appears that DC is in conflict with other uses of metadata (such as those of intellectual property holders). However, analysis has shown that many shared requirements exist. To enable the identification of common requirements, the various users of metadata need a common conceptual model. An IFLA semantic model, presented in "Functional Requirements for the Bibliographic Record1," provides a meeting point for what had at first seemed two very different perspectives. This article provides an outline for promoting consensus on the structure and relationship of Dublin Core metadata and Rights Management metadata, but our hope is that this structure may be appropriate for groups and projects beyond those currently involved in these discussions as well.

Working together to define common requirements and articulate common metadata structures benefits both communities. The same information objects (books, journals, articles, sound recordings, films, and multimedia, in physical or electronic form) are encountered in traditional library and commercial environments2. Indeed these two worlds intersect continuously when resources are acquired for library collections. A shared standard for core discovery metadata that integrates easily into future information use models has great benefits for interoperability across domains and for information interchange.

I. Background

I.a The Dublin Core in 1998

Readers of D-Lib will be familiar with the process that led to the Dublin Core Element Set. Focussed on requirements for improved information discovery in the networked environment, the DC initiative grew out of a process of debate and consensus building3. The DC effort has attracted a broad cross section of resource description communities, including libraries, museums, government agencies, archives, and commercial organizations. International interest has led to translations of the Dublin Core to 20 languages thus far. It has drawn its strength from the diversity of communities represented, and the ability to bridge many differing perspectives and requirements.

What began as an effort to identify simple semantics for resource discovery has generated wide recognition of larger information architecture issues. Well before the 5th Dublin Core workshop in Helsinki (October, 1997),4 it was recognized that the Dublin Core needed to accommodate more specific metadata than could be supported by the basic model of 15 elements containing strings of text as values.5 The semantic refinements of qualifiers and substructure, present to some degree in all DC applications, required a more sophisticated underlying representation. Using "dot notation" in HTML6 to achieve this has helped to jump-start many early applications of Dublin Core, and is in some ways responsible for progress made so far. However, the inherent structural limitations of HTML assured that broad-scale interoperability and interchange of structured metadata would never be satisfactory for anything but very simple resource description. The broad adoption of at least some qualifiers in virtually all Dublin Core applications to date attests to the wide acceptance that qualifiers are a necessary addition to the resource description landscape. Implementers need the additional power of specification and substructure that qualifiers afford. It is clear that a conceptual model is necessary to support the broad spectrum of semantic requirements expected by implementers (from very simple to highly structured). In addition, the conceptual model needs to recognize that the metadata requirements are not static and must allow for graceful changes as the DC standard evolves.

A Data Model Working Group7 was constituted following the Helsinki meeting to address these issues. It was in part the efforts of this group that has highlighted some inconsistencies in the formulation of the basic element set. For example, the element "Source" records a specific type of "Relation" between two information objects; the elements "Creator", "Publisher" and "Contributor" can be usefully thought of as types of Agents.8 Several groups running workshops on how to use Dublin Core metadata with practitioners also reported confusion among users as to how to choose between these elements, suggesting that there are practical as well as theoretical reasons to revisit the structural foundations of the Dublin Core.

At the same time as these more sophisticated requirements began to be expressed within the DC Community and a model was being developed to support them, the Dublin Core Initiative was criticized by others concerned with the limitations of basic DC semantics for expressing their requirements. These limitations were of particular concern when DC metadata is seen as a core drawn from a broader metadata universe designed to support particular applications or uses that may begin (but do not end) with information discovery. Thus the challenge to the DC community is how simultaneously to support the current users of DC while ensuring that the development of DC enhances interoperability between metadata sets and communities.

I.b Rights and Publishing Metadata in 1998

In the first half of 1998 a number of leading international intellectual property rights owners’ organizations came together with a common technical aim. They had recognized that in the digital environment the traditional distinctions between market sectors (such as records, books, films, and photographs) were collapsing into a common "content" environment where different rights were traded (or, where appropriate, given away freely) in increasingly complex ways. The various identifiers used by these sectors9 needed to work together, with their accompanying metadata.

The INDECS (Interoperability of Data in E-Commerce Systems)project was established to integrate a number of sectoral initiatives. These include the copyright societies’ CIS (Common Information System) plan, the record industry's ISRC and MUSE project, the audiovisual ISAN initiative, the text publishing industries' ISBN and ISSN and the Digital Object Identifier (DOI). It is designed as a "fast-track" process, to develop a number of specific common standards and tools that enable interoperability of identifiers and metadata.

The INDECS project has the backing of the international trade bodies of many major content provider groups including IFPI (recording industry), CISAC and BIEM (copyright societies), IPA and STM (book publishing), IFRRO (reprographic rights) and ICMP (music publishers), all of whom are affiliated, and constituent members of which are the active partners. Its sponsors also include the International DOI Foundation. It has a formal evaluation procedure including an open conference in London in July and culminating in a final approval committee to be held at WIPO in Geneva in October 1999.

The INDECS project is concerned with the same resource discovery elements as Dublin Core, but in addition embraces metadata for people (human and legal) and intellectual property agreements and the links between them. Its basic model has evolved from the copyright societies' CIS plan, initiated in 1994 and the initiator of the ISO proposals for the International Standard Work Code (ISWC) and International Standard Audiovisual Number (ISAN). INDECS has a simple rubric expressing its underlying commerce model: People Make Stuff, People Use Stuff, and People Do Deals About Stuff.

Each of these three primary entities and the links between them -- People ("Persons", whether natural or legal), Stuff ("Creations", whether tangible, spatio-temporal or abstract) and Deals ("Agreements" between persons about the use of creations) -- requires unique identifiers and standardised descriptive metadata.

Based on work already established within the CIS Plan, INDECS has developed a first draft of its detailed generic metadata model integrating these three entities in a way that may be applied to any type or combination of creation or agreement. The model also attempts to elaborate a comprehensive set of high-level semantics for rights-based metadata. Some of the work of the project will be taken up with the mapping of the model and its semantics against the various constituent identifiers and metadata sets.

In preparation for the project, which began formally in November 1998, the INDECS technical co-ordinator Godfrey Rust voiced concerns about the limitations of DC, that were published as part of an article in the July 1998 D-Lib [http://www.dlib.org/dlib/july98/rust/07rust.html] that also outlined elements of the INDECS model. Weaknesses in the unqualified fifteen element Dublin Core as seen from the perspective of INDECS requirements, include the arbitrary separation of Creator and Contributor, the ambiguity of Publisher, the confusion of Source and Relation, the limited definitions of Date and Rights, the absence of a "Size" element (an "Extent" in INDECS terminology), the vagueness of the DC definitions, and a bias in its terminology towards text-based resources.

More significantly, given the desire to see a discovery element set within a larger process, Rust felt the Dublin Core did not recognize the inherent complexity of "creations" that are commonly made up of a network of constituent elements each with its own "core" metadata and rights. The flat fifteen elements of DC, which are important in its widespread acceptance, may be too limiting in some important contexts.

But the heart of the matter lay in another kind of dependency. One thing that had emerged clearly from the CIS/INDECS model is that effective rights metadata ("agreements") are heavily reliant on well-structured descriptive resource metadata of the kind identified in the DC core set, and set out in related but somewhat different terms in the INDECS analysis. Without unambiguous identifiers and classifications, rights cannot be securely protected or granted. The terms of agreements are dependent (among other things) on the identity and characteristics of the works owned or traded. For example, the precise role of a Contributor, Creator or Publisher, the Date and Place of creation or publication, the Format, Genre or Subject of a work are all elements that may affect rights ownership, licensing or royalty entitlement. Because this descriptive metadata is an integral part of rights metadata, Rust argued the two have to be tightly-structured to interoperate.

Rights owners need well-structured metadata for their electronic resources, but it does not make sense to develop a separate standard. No one wants to maintain parallel sets of metadata for different functions, particularly when the function of discovery is so closely tied to commerce and other uses. Rights owners, like all those involved in metadata management, are seeking the best models for creating, storing, using and re-using metadata for many purposes.10 Despite the apparent difficulties, INDECS, not wishing to re-invent existing wheels, would much prefer to find common ground now with DC than face a proliferation of overlapping standards in the future.

Harmonisation should also bring substantial benefits for the DC community, which requires "people" identification systems and licensing mechanisms as much as the creators and rights owners. The models are neutral on the matter of rights and commercial terms: whether usage is free or paid for, the chain of rights enabling the user to use a given resource requires identification, for the security of user and owner alike.

I.c Seeking Rapprochement

The Web environment offers the possibility for the general distribution of authoritative metadata, associated with a resource at the time of its creation. Organizations could be attracted to using the Dublin Core for discovery (even if their primary interest is to create metadata for data exchange, income collection or rights management) if a broad standard for descriptive metadata in the Web environment supported the activities that are the motivations for discovery. The Warwick Framework, which grew out of the second Dublin Core workshop, already reflected the DC community’s recognition of the need for distinct but inter-related metadata packages, that enabled interoperation beyond discovery alone.11

The opportunity to seek common solutions with other groups who are working on metadata, including rights holders, and in the process to clarify implications of the DC model for Dublin Core users, led to discussions between representatives of the DC and INDECS/DOI communities at DC-6. Initial technical discussions (in September of 1998) revealed many commonalities in requirements, including the likelihood that each could be expressed using the Resource Description Framework (RDF). A subsequent meeting immediately prior to DC-6 further strengthened these understandings and began to identify specific semantics that would benefit from mutual attention. The results of these discussions were well received at a joint meeting of the DC-Technical Advisory Committee and DC-Policy Advisory Committee immediately prior to DC-6. A presentation to a plenary meeting of DC-6 itself introduced the collaboration to the DC community. During and after the meeting, the authors continued to explore areas of possible commonality. A more fully elaborated version of a possible framework was presented to the Data Model Working Group immediately following the DC workshop, to ensure that the semantics under discussion could find common expression. Thus the concepts described in this paper represent work in progress, which will require detailed scrutiny by the DC, DOI, and INDECS community.

II. A Logical Model of Common Semantics

II.a Developing a Logical Model

The start point for a common understanding which began to emerge at DC-6 between the DC and INDECS/DOI approaches was a shared appreciation of a third piece of metadata analysis: the recently published, but long gestating, IFLA Functional Requirements for the Bibliographic Record (FRBR). The INDECS entity relationship analysis, although broader in scope as it embraced rights as well as resources, had already quite independently reached similar conclusions to the FRBR, and many in the DC community had recognised the FRBR's potential value.

Translating both the INDECS requirements and the DC requirements into the IFLA model provided the framework of a common logical expression for the two perspectives. It reveals a substantial, probably complete, overlap between the scope of INDECS metadata requirements (in relation to resources) and the scope of metadata requirements in Dublin Core and its emerging qualifications. Common semantics can be identified for each metadata element. More detailed, application-specific semantics will need to be articulated, though, not just for these two broad communities, but for other communities and for implementations within them. We believe that by sharing a common higher level semantic framework, both communities can support a high level of interoperability.

II.b The IFLA Model

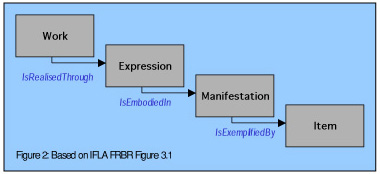

The working method we adopted was to use the IFLA FRBR model as a common logical model for metadata. This model has as its focus an information resource in one of four "states". In this model, an original creator conceives a WORK. The work is an abstraction. It must be realized through an EXPRESSION. The same work may be realized through numerous expressions -- as when two directors produce the same WORK. Each EXPRESSION may be embodied in one or more manifestations, as when we have the printed script, the video of a performance of the play and an audio-CD of the performance of the musical numbers. When MANIFESTATIONS are mass-produced, each MANIFESTATION may be exemplified in many ITEMS (typically called copies).

Many WORKS find a single EXPRESSION in only one MANIFESTATION. Some very successful WORKS are expressed in many genres and/or performed at many times and may be produced in numerous MANIFESTATIONS. Many unique information resources, such as museum objects, or natural specimens are not "copies" of mass produced manifestations. We believe that with further careful thought and consultation the DOI/INDECS and DC communities can agree fully on fundamental categories of information resources based on this analysis.

FIGURE 2: Works, Expressions, Manifestations and Items [based on IFLA FRBR Figure 3.1] [Cardinality is expressed here with arrows.]

We proposed two significant clarifications to the FRBR analysis for our purposes. The first was to recognise that an item is a type of manifestation, albeit an extremely important one. The second overcomes, we believe, what had seemed a common confusion about the nature of an Expression. An expression, we propose, is a creation which exists in space and time (identified, if it is public, as a performance), but not in tangible form. The INDECS model provides a number of ways of describing the structural differences between the main creation types:

ABSTRACTION

EXPRESSION

MANIFESTATION/ITEM

Work

Performance

Carrier

Concepts, thoughts, ideas

Actions

Atoms, bits

Abstract

Spatio-Temporal

Tangible

"I conceived it"

"I did it"

"I made it"

This analysis falls out naturally to the INDEC/DOI community as each of these "creation types" gives rise to a different set of rights. Perhaps the clearest example is of an audio or audiovisual CD (manifestation) which contains recordings of performances (expressions) of songs (abstract works). Each of these entities has different identities (UPC/EAN, ISRC, ISWC) and metadata and, commonly, different rights owners. In textual or static visual works the identification of the "expression" which gave rise to the manifestation of the resource (the act of creating this draft or version) may be less evident or important, but our analysis at this stage suggests that it is no less real or central to an understanding of the effective organisation of metadata.

The two communities have no common view as yet about the adequacy of the second part of the IFLA model, which relates the bibliographic resource to people and organizations responsible for its creation, expression, distribution and ownership. The IFLA model [expanded further in figure 3 below], reflects the library community’s traditional interest in the creation of works and the ownership of physical works. It does not adequately represent the interest of the INDECS community in the ownership of intellectual property rights. Intellectual property rights arise from initial creation (though they may depend on what specific kinds of creation -- origination, compilation, excerpting, media transformation, replication), but they can be transferred from one person or organization to another independently of the ownership of a physical item.

FIGURE 3: People, Organizations, Works and their Expressions [based on IFLA FRBR Figure 3.2]

II c. Enhancing the IFLA Model

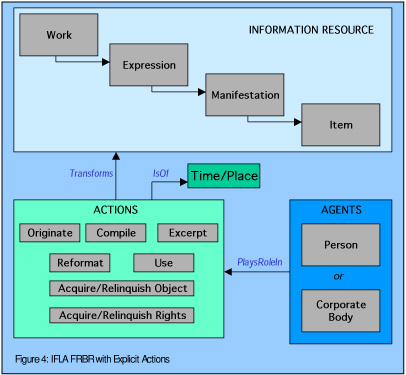

We propose the explicit representation of an ACTION as an enhancement to the IFLA model. This is missing in the IFLA model, but is needed to recognize the transferability of ownership (of both rights and objects) and to acknowledge the multiplicity of roles that Agents play with respect to information resources. Figure 3, below, shows ACTIONs within the model, taking place in a specific time and place.

FIGURE 4: Integrated Expression of DC and INDECS Semantics for Agents, Actions, and Resources

ACTIONS support another element missing in the IFLA model, the role instruments may play in the creation and dissemination of information resources. People have created many devices (such as the Hubble Space Telescope, weather satellites or robocams) that automatically create, or automatically distribute, information resources.

It is not sufficient, however, to articulate only who created, realized, produced or owned a work, expression, manifestation, or item, or the rights thereto. Both communities are further interested in describing what IFLA calls the "Subject" Relationship attributes of WORKS. The IFLA model recognizes that WORKS may have as their subject:

1) works expressions, manifestations or items

2) persons, organizations and instruments

3) concepts, objects, events, or places

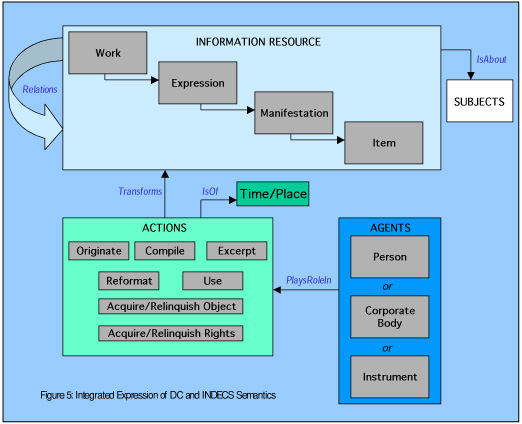

The DC community has gone a step beyond "Subject Relations" (something is "about" something else) and records what might be called "Object Relations" (something is "made of", or "part of" something else). In some communities dealing with informational resources, particularly those concerned with images, museum objects, and archives, these "of-ness" relations are extremely important. They fall into two classes -- provenance and coverage.

With these extensions of the IFLA model, we feel that we have a strong basis on which to construct any divergent, discipline- or domain-specific, metadata sets including extensions to DC and INDECS. The common model enables us to share what we feel we hold in common.

FIGURE 5: A High Level Model for DC and INDECS Semantics

III. Using the Model

We've been pleased to find that this simple, high-level model is capable of explaining quite a few things that were intriguing or troubling to the DC community before it was developed. Some of these questions are discussed below, as examples. For the INDECS community, some of whose members have identified resources in categories similar to these for many years as different rights and rightsholders apply to the different levels, the analysis provides an invaluable point of convergence with the bibliographic tradition.

III.a Relations

At and following the Dublin Core workshop in Helsinki, a "Relations Working Group" considered a wide range of possible relations between information resources. Following an analysis, the group arrived at five reciprocal relations:12

- References / Is Referenced By (to point to other information resources)

- IsBasedOn / IsBasisFor (to express intellectual derivation)

- IsVersionOf / HasVersion (to express historical evolution)

- Is Format Of / Has Format (to identify transformations of media or layout)

- Is Part of / Has Part (to record Part/Whole)

During the DC/INDECS discussions, and in efforts to articulate a representation in XML/RDF, other relations were determined to be required, including:

- Is [to express that something is original or sui generis]

- IsMetadataAuthorOf / HasMetadataAuthoredBy [to name the creator of the metadata]

- IsDefinitionOf / IsDefinedBy[to point to the URI of the definition of the semantics]

- IsOwnerOf/ IsOwnedBy [to name the owner/repository with custody of a physical thing]

None of these "Relations" require any further elaboration of the model, for each is, in some way, a reflection of the extensions we made earlier to the IFLA model:

- Is

reflects our introduction of the concept of natural, or non-bibliographic, items.

- IsMetadataAuthorOf

reflects the need for the explicit recording of the person or organization responsible for the content of a metadata set.

- IsDefinitionOf

reflects the need for metadata to be specifically defined within the context of a particular intellectual schema; it exists in an information universe and needs to carry the address of its name space.

- IsOwnerOf

reflects the need to track physical custody separately from intellectual property rights (the latter are described by the fifteenth DC element, and aim to be comprehensively covered by the "agreements" structure in INDECS/DOI).This articulation of relationships and their types, helps resolve several issues within the Dublin Core community, five of which came to the fore during the most recent workshop in Washington (each discussed further below):

1) the problem with separate metadata elements for Creator, Contributor, and Publisher, as all are Agents related to Works, Expressions, Manifestations or Items

2) the confusion between Genre and Format, as both are Form, related to either Work/Expression or Manifestation/Item

3) the many qualifiers that have been proposed for Date, as a Work, its Expression, a Manifestation and an Item can each have a particular Date

4) the apparent redundancy of the element "Source", as Source is expressed more clearly as a particular Relation

5) the reasons for the 1:1 relationship between metadata and an information resource and why application of this principle seems to lead to confusion.

III.b Agents

The terms Creator, Contributor and Publisher are often used as if they roughly correspond to the relationships between an Agent and a Work (he wrote this play), an Agent and an Expression (she acted in this play), and an Agent and a Manifestation (they published this script). However, the Creator, Contributor, Publisher distinction does not provide a fine enough classification to specify such vastly different roles as editor, composer, or actor, or distinguish these roles from others with a lesser creative impact on a manifestation such as typographer, foundry, or audio engineer. Nor do Creator/Contributor/Publisher permit us to specify the owner and rights owner(s) of an item. Finally, without a fairly tortured usage, they do not allow us to identify devices involved in creation and dissemination of information resources. By combining the various types of Agents, we can assign them roles from a vocabulary scheme that has all the variation required in each application.

III.c Form (DCType and Format)

As recognized in the IFLA model, the concept of "Form" is problematic unless we are careful about whether we are speaking of the form of the "Work", the "Expression", the "Manifestation"/"Item". English had to borrow a concept for the "form" of a work or expression from the French language term genre. These kinds of descriptors have been referred to in Dublin Core discussions as suitable for recording in DCType.

The "physical form" of a manifestation or item is often called "format" and was assigned a separate element in the 15 element Dublin Core. Unfortunately, in English again, the actual terms used to name genre and format are often identical (such as photograph, drawing, film). Clarifying whether the term qualifies a work, expression, or a manifestation/item, can prevent confusion between homonyms, and aid in the distinction between these two DC elements.

III.d Date

The Dublin Core Date Working Group has heard arguments for many qualifiers to be applied to the Date element. Refinements have included date written, date performed, date published, date issued, date valid, date recorded, etc. All are dates of particular actions; describing when a person did something in relation to a resource. The IFLA model does not entirely eliminate this confusion, and cannot because it does not separately identify the entity "Action."13 If Actions are explicitly documented as part of the model, unqualified dates can be explicitly tied to acts of creation, arrangement, performance, dubbing, release, etc. This is much clearer than seeing these dates as properties of the information resource itself, where they lose their meaning without qualification.

III.e Source

Before the articulation of the "Relation Types", the Dublin Core workshops defined a metadata element "Source" as: "A string or number used to uniquely identify the work from which this resource was derived, if applicable. For example, a PDF version of a novel might have a SOURCE element containing an ISBN number for the physical book from which the PDF version was derived." The Source element could therefore record any of the relations IsFormatOf, IsBasedOn and IsVersionOf.

The example given actually refers to the Identifier (ISBN) of a Manifestation (physical book) from which another Manifestation was derived. But the "Identifier" of the PDF file could be considered to be the same ISBN. More accurately, we need to indicate that the physical book is a Manifestation of a particular Expression of a Work, while the PDF file is a different Manifestation of the Manifestation (physical book).

III.f "1:1"

One of the most difficult issues for implementers of the Dublin Core has been defining logical clusters of metadata (called "metadata sets" during the Helsinki workshop). A "logical cluster of metadata" refers to one occurrence of the fifteen repeatable DC metadata elements, referring to a particular state of an information resource. In discussions at the Helsinki DC meeting, we found this concept of metadata clusters or sets clarifying and avoided confusing it with "metadata records" -- e.g., the physical record in a specific implementation, which could contain many logical clusters of metadata (as a nested hierarchy for example). Each cluster references one, and only one, state of the information resource -- the elements that it contains describe that instance. We referred to this as the 1:1 principle, and the resulting clusters as embodiments of 1:1 structures. An implementation system can respect 1:1 structures even when a single physical record in that system may describe the Work, its Expression, a Manifestation, and even other Works that are related to it.

The model proposed here makes it clearer that multiple Agents and Actions may be related to a Work, its Expression, a Manifestation or an Item. The metadata about these relations must, therefore, be kept discrete. Traditional bibliographic control systems have not handled well the implicit or explicit linkages among entities, primarily perhaps due to technological limitations. The Web, however, for which linkage is the dominant underlying metaphor, solves the technological problem. We now have the means to document and execute complex semantic relationships, but are without a body of best practice to guide us. The IFLA Model makes the logic of 1:1 structures clearer, and may help resolve this problem.

If metadata is exchanged using 1:1 expressions, different metadata authorities can create different parts of the metadata: the publisher can report publication metadata; the rights owner can report rights metadata; and the author or an information provider can report metadata about the work. Those who document a particular performance of a play or work of music can confine themselves to reporting the many individuals involved in this expression, and "point to" or reference metadata about the work or works performed. Music distributors who release the performance on CD, on tape, and in a RealAudio file, can confine themselves to describing these three Manifestations. Indeed, in considering a complex multimedia object containing hundreds or thousands of component "creations", it is impossible to see how adequate metadata could be assembled by any other means.

This recognition of the "modular dependence" of metadata lies at the heart of the INDECS project. Because each of the different resource types attract different rights and rights holders, the "1-to-1" identification and description of components of a single creation has long been recognised as sine qua non for e-commerce metadata.

It is important to envision how these various metadata sets might be reassembled into a human readable form, or how a "record" might fully contain everything that a user might want to find out about a particular manifestation of a work. Depending on the local implementation, this information might be held in a single "record" or a number of related (or hierarchically structured) records. Each implementation will have a different interfaces, and there may be different views of the data for input and searching. But for metadata to be interchanged among systems unambiguously, the relations implicit in local systems must be made explicit (for not all implementations will be constructed on the same assumptions, particularly when interchange is cross-domain). A common record syntax is required; both INDECS and the Dublin Core have been exploring the Resource Description Framework (RDF) as a means to carry complex metadata.

In order to build tools that function predictably across millions of metadata sets created in different environments, these metadata must have the same structure and explicit relations. The proposed RDF expression of the Dublin Core (discussed further below) offers a syntax for recording complex relations. It ensures that one metadata element is about one logical or physical thing, and that the relation between that thing and other things is noted explicitly using Relation Types. It then becomes possible to "operate" or trigger actions based on these relations. A rigorous structure helps retrievability too, because it makes it possible to search for an individual whether they made a work or a part of a work. And it makes it possible to collocate all the possible digital manifestations of a work by tracing their relation back to the work. The 1:1 rule, then represents a logical simplification, but at the cost of system complexity. As tools to support RDF become widespread (a reasonable expectation, given the indications that industry support for RDF is increasing rapidly), implementing such systems will seem much less difficult. At this stage in the collaboration the possibility that the DC model may be extended to meet the requirements of the INDECS/DOI community, and in doing so enable for itself a new range of functionality, is an attractive consideration. The alternative -- independent and incompatable models -- is equally unattractive.

IV. A Common Syntactic Model - RDF

The Resource Description Framework (RDF), developed under the auspices of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C),14 is an infrastructure that enables the encoding, exchange, and reuse of structured metadata. This infrastructure promotes metadata interoperability by helping to bridge semantic conventions and syntactic encodings with well defined structural conventions. RDF does not stipulate semantics, but rather provides the ability for each resource description community to define a semantic structure that reflects community requirements. RDF can utilize XML (eXtensible Markup Language) as a common syntax for the exchange and processing of metadata.15 The XML syntax is a subset of the international text processing standard SGML (Standard Generalized Markup Language) specifically intended for use on the Web. The XML syntax provides vendor independence, user extensibility, validation, human readability, and the ability to represent complex structures. By exploiting the features of XML, RDF imposes a structure that provides for the unambiguous expression of semantics and, as such, enables the consistent encoding, exchange, and machine-processing of standardized metadata.

RDF supports the use of conventions that will facilitate interoperability of modular metadata sets and their reuse within community defined semantics. These conventions include standard mechanisms for representing semantics that are expressed in a simple, yet powerful, formalism. RDF additionally provides a means for publishing both human-readable and machine-processable sets of properties, or metadata elements, defined by resource description communities.

The Dublin Core Data Model Working Group agrees that RDF provides adequate flexibility and functionality to fully support encoding DC metadata. Early implementation prototypes and the thinking of a substantial cross section of metadata implementers and theoreticians suggest that this assertion will stand up to the test of practical implementation. The broad scope and flexibility of RDF makes it desirable, however, to define conventions for structuring metadata to maximize the potential for interoperability.

The Dublin Core Data Model applies RDF as an enabling mechanisms, providing consistent guidelines to support Dublin Core applications. It declares the semantics defined by the Dublin Core community using RDF Schemas. To avoid confusion, and be explicit when combining semantics from multiple domains, or "namespaces", a namespace identifier token (i.e., "dc") is prefixed to each element in order to identify it uniquely; the element <dc:Title> would be interpreted as "the "Title" as defined by the Dublin Core Community". <dc.Title> could then appear in a number of different applications, maintained by publishers and libraries for example, and still be recognized as equivalent.

Namespaces also facilitate meeting the requirement for additional substructure or qualification within DC. The Data Model Working Group recommends that qualifiers be managed under a separate, but closely related namespace: Dublin Core Qualifiers (DCQ). This compartmentalization will facilitate modular accommodation of different levels of Dublin Core. Applications accommodating only the 15 Dublin Core elements without qualifiers need recognize only the Dublin Core namespace; additional complexity can be provided in a modular fashion with the addition of DCQ.

FIGURE 6: RDF expression of Qualified and Unqualified Dublin Core, using dc:Date

RDF encourages this type of semantic modularity by creating an infrastructure that supports the combination of distributed attribute registries (i.e., multiple namespaces). Thus, a central registry is not required. This permits communities to declare element sets which may be reused, extended and/or refined to address application or domain specific descriptive requirements. The rights holding community can therefore declare an additional set of elements to support the detailed documentation of rights transfer agreements (or deals). This Deal-making metadata may make use of some DC elements, which could be recognized by DC applications. Building a modular rights package of metadata onto a DC discovery set would avoid redundancy, and enable a DC-aware application to discover where a particular work may be affected by rights restrictions. Resolving those rights would require an awareness of the rights metadata and the rules for its processing.

V. The Process for Moving Forward

The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative evolved as a loose association of interested stakeholders and practitioners. As interest and recognition in DC has grown, and the constituencies that the initiative serves have broadened, it has become increasingly evident that a formal process is necessary to promote stability (by way of standardization) and support evolution as the effort matures. The goals of such a process include maintaining the coherence of the DC element set, while assuring both broad representation of the perspectives of various sectors and disciplines, and international input. The culture of the Dublin Core initiative is strongly imbedded in consensus building; the emerging DC Process Guidelines16 will validate that process.

The Process Guidelines being developed are based on the identification of work items from a wide variety of sources, and their assignment to open working groups. Proposals for solutions are vetted by open community discussion and ratified by a Technical Advisory Committee and a Policy Advisory Committee. The Dublin Core Directorate (based at OCLC) administers these committees and maintains a website that constitutes the repository of decisions and supporting documents.17

The integration of the conceptual data models for DC, INDECS, and IFLA is one of the first work items to be developed de novo under the new Process Guidelines. The Schema Harmonization Working Group represents a significant early challenge for this process, requiring as it will some changes to the Dublin Core which will have ramifications for existing applications. It will be necessary to manage changes to ensure that the functional requirements of each of the represented communities are accommodated, and the least possible disruption is made to current practice. As a practical matter, these objectives are likely to be met by engineering a new Dublin Core version that is backwardly compatible with existing applications, while supporting a more robust data model expressing the common requirements of DC and INDECS/DOI. Early discussions among the stakeholders suggest that this is a realistic goal.

Change inevitably causes uncertainty and, and uncertainty leads to instability. The benefits and costs of such change must be considered carefully, and if changes are to be made, they must be introduced with the minimum possible disruption to existing applications. In the present case we may reassured somewhat by the fact that the semantics of what we hope to be able to say about resources is not changing significantly. Rather, it is the structure of how assertions are made that is in question. The objective is to structure metadata assertions using a general model with greater flexibility than the implicit ad hoc model that has evolved in the past. The clarification of the model will allow the resulting metadata to be simpler and clearer (and thus, more likely to be consistent from application to application).

Recent Web history gives us cause for reassurance. HTML is deeply flawed as a markup language, mixing as it does procedural markup (where to put dots on the screen) with structural markup (what is the function of an entity). It is nearly useless for purposes of serious publishing, and could only be made to be parseable SGML through the contorted efforts of a year of standardization effort. It is, nonetheless, one of the cornerstones of the success of the Web, and its evolution through several versions and metamorphosis into XML have brought to the Web a more mature markup idiom that will meet the demands of far more sophisticated applications than were practical just four years ago. It is significant to note that most Web software continues to do a reasonable job at rendering the early versions of HTML as well as its descendents.

The Dublin Core can be thought of as the HTML of Web metadata. It is crude by many resource description standards, an affront to the ontologists, and suffers some of the foibles of committee design. Notably, it is useful, and it is this useful compromise between formality and practicality on the one hand, and simplicity and extensibility on the other that has attracted broad international and interdisciplinary interest. The growing base of legacy applications need not be abandoned, even as more sophisticated applications are developed. Careful attention was invested in making the transition of HTML versions as smooth as possible. Similar attention will be paid to making changes in the Dublin Core minimally disruptive.

The process being established to govern the evolution of the Dublin Core Initiative is the guarantee that this transition can be made with the broad interests of the community always at the fore. The Dublin Core Initiative is at is heart an open and populist endeavor. It succeeds on the efforts of many dozens of committed stakeholders that work together in a co-operative spirit of compromise. The formalization of the effort is taking place with the goal of retaining this spirit of pragmatic consensus building.

VI. Conclusions

Libraries want to share content; publishers want to sell it. Museums strive to preserve culture, and artists to create it. Musicians compose and perform, but must license and collect. Users want access, regardless of where or how content is held. What all of these stakeholders (and more) share is the need to identify content and its owner, to agree on the terms and conditions of its use and reuse, and to be able to share this information in a reliable ways that make it easier to find. An infrastructure for supporting these goals is now emerging, and the prospects for broad agreement on how to support these shared requirements has never been brighter. But new technology does not solve our problems or resolve our differences. It simply makes it possible for us to address the problems more clearly.

By exploring the development of a shared conceptual model, and its expression in a common syntax, the DC and INDECS/DOI communities have affirmed the value of creating and interchanging modular metadata sets. Just as creative works move through a process, from their creation, distribution, discovery, retrieval and use, so too will their metadata need to be interchanged in order to support these functions in an integrated environment of networked information.

Simple resource description was among the primary motivations for embarking on the development of the Dublin Core. The idea of an intuitive semantic framework that anyone –- from creators of the work on the one hand to a skilled cataloger on the other –- could use to describe resources is appealing. The modeling described in this paper seems to fly in the face of this goal of simplicity. It is often the case, however, that simplicity can only be achieved through detailed engineering that helps to mitigate the underlying complexity of a problem. Lego(tm) is child's play. Any three year old can use them. But the interoperability of Lego blocks across 6 decades (and that satisfying "click" as they snap together) is the result of precise engineering to tolerances that approach those necessary for internal combustion engines.

The authors assert that coping with the broad spectrum of complexity expected of metadata applications in the future requires this same sort of engineering. A sound underlying model will help achieve the broadest possible interoperability, from simple embedded metadata on the one hand up through the intricacies of complicated, multi-functional descriptions.

The potential benefits of reconciling these closely related sets of requirements are great. It will be difficult otherwise over the next few years to ensure that each community with somewhat distinct needs does not invent incompatible metadata models for achieving what are fundamentally overlapping objectives. Educators have proposed models, as have stakeholders in electronic commerce. It is of paramount importance that we identify common frameworks for exchange of information, and to recognize where requirements converge. The needs of various stakeholders are often different, and frequently conflicting. Nonetheless, all may benefit when the frameworks for expressing descriptions are interoperable.

The immediate audience for this paper comprises the current DC constituency more than that of INDECS or DOI, so it has concentrated more on the issues which this collaborative work has on DC. However, in parallel with the DC process, the INDECS and DOI initiatives are on their own fast track, and while developing their technical proposals and consolidating consensus within their own communities, they face the same issues as DC with cross-sector co-operation. The needs, governance, objectives and timetables of each of our communities needs to be respected by the others if common Web metadata standards are to be broadly successful.

The Dublin Core Working Group on Schema Harmonization will be working on these issues in conjunction with the INDECS project. The leaders of these groups will seek out the most effective mechanisms for co-operation. At the same time there are initiatives in other communities, including developments related to the DOI and other international standard identifiers. We welcome the participation of others interested in ensuring that our conceptual models and the tools developed from them support the interoperability we all desire in the networked information universe.

VII. Notes[Note 1] < http://www.ifla.org/VII/s13/frbr/frbr.pdf>

[Note 2] For the purposes of discussion we have oversimplified the divisions between the "bibliographic" community of those who manage information resources after their creation, and the "rights owners" community of those whose interests are in the commercial exploitation of intellectual property. The lines between these groups are much less clear than are portrayed here, and most individuals and organizations will at some point play all the roles of information creator, information user, and information repository.

[Note 3] Regular reports of the DC workshops have been published in D-Lib; they can also be found linked to the DC Web site at <http://purl.org/DC/about/workshop.htm">.

[Note 4] See Stuart Weibel and Juha Hakala, "DC-5: The Helsinki Metadata Workshop: A Report on the Workshop and Subsequent Developments" in D-Lib, February 1998, <http://www.dlib.org/dlib/february98/02weibel.html>.

[Note 6] Suggested in Canberra as "The Canberra Qualifiers." See <http://www.dlib.org/dlib/june97/metadata/06weibel.html>.

[Note 7] < http://purl.org/dc/groups/datamodel.htm>.

[Note 8] The decision to define three categories rather than identify roles within a more general category dates from the first workshop. In the absence, at that time, of any explicit method to express roles within a more general category, it was decided to sweeten broad acceptance of DC with what Terry Allen then called "syntactic sugar." Subsequent formalization of the data model, and the experience of a number of groups who have had difficulty teaching the distinctions to catalogers, led to the "Agents Proposal" which was discussed at DC-6. <http://www.archimuse.com/dc.agent.proposal.html>.

[Note 9] Such as the ISBN (International Standard Book Number), ISSN (International Standard Serial Number), ISRC (International Standard Recording Code), ISAN (International Standard Audiovisual Number), ISWC (International Standard Work Code) and the newly-developed DOI (Digital Object Identifier).

[Note 10] As Dublin Core was "the only game in town" for Web metadata, rights owners were beginning to view the Dublin Core as precisely that, and were either starting to use it inappropriately as a set of entities on which to model their databases, or to ignore it entirely because of its inadequacy for the same purpose.

[Note 11] See Lorcan Dempsey and Stuart L. Weibel, "The Warwick Metadata Workshop: A Framework for the Deployment of Resource Description," D-Lib Magazine, July/August 1996, <http://www.dlib.org/dlib/july96/07weibel.html>.

[Note 12] See the Relation Working Group report at < http://purl.org/dc/documents/working_drafts/wd-relation-current.htm>.

[Note 13] The IFLA document defines the attribute Date of the Work as: "The date of the work is the date (normally the year) the work was originally created. The date may be a single date or a range of dates. In the absence of an ascertainable date of creation, the date of the work may be associated with the date of its first publication or release."

[Note 14] The RDF has the status of a proposed recommendation of W3C, see: <http://www.w3.org/TR/PR-rdf-syntax/>.

[Note 15] RDF is a simple yet powerful data model predicated on the notion of triples (resource, property, value) which is based on classic research. Generally the utility of this abstract data model, however, requires some syntax for transmission across the wire. For a variety of reasons we (in this case the W3C) have chosen XML as this syntax, but this is not a requirement of RDF per se. Sony Research is using RDF for describing HDTV broadcasts using their own proprietary syntax. Nokia is additionally using RDF instance data in a compressed binary format for strictly bandwidth transmission issues, etc.

[Note 16] Available on the DC web site at < http://purl.org/dc/>.

[Note 17] <http://purl.org/dc/>.

Copyright © 1999 David Bearman, Eric Miller, Godfrey Rust, Jennifer Trant, and Stuart Weibel

Correction made to ISWC hyperlink and INDECS URL removed at the request of the authors, The Editor, January 19, 1999 9:10 AM.

Top | Contents

Search | Author Index | Title Index | Monthly Issues

Previous Story | Next Story

Comments | Home| E-mail the EditorD-Lib Magazine Access Terms and Conditions

DOI: 10.1045/january99-bearman